Fact-checking truths behind the viral invasive Joro Spider

(WPDE) — You may have seen headlines going viral about an invasive spider making their way to our area.

In an effort to clear up some unnecessary panic, Dr. David Coyle, who works with the Dept. of Forestry and Environmental Conservation at Clemson University, shared some insight into these foreign arachnids.

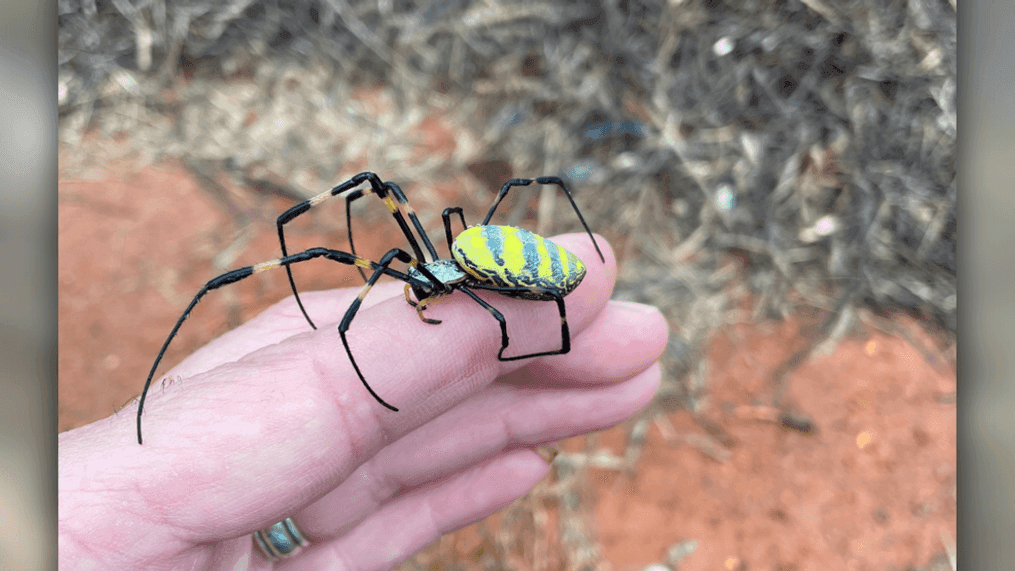

What you're seeing here is a Joro Spider, native to China and Korea.

They first were documented in northern Georgia in 2014, but they were probably there a few years before that," explained Coyle, visibly frustrated with the numerous over-dramatized headlines surrounding these spiders. "They more than likely just hitch-hiked over on cargo ships from China or Korea, and made their ways on containers from there.

Transportation like large cargo containers are a common way invasive species make their way into the United States.

Just last year in the Northeastern part of the country, Asian Long Horned beetles, Box Tree Moths and the Spotted Lanternfly all made their way here in similar fashions.

RELATED:Threesome of invasive pests pose threat, public urged to scrape, squash, stomp, report sightings

As of June 2024, the Joro Spiders have their largest population in the United States right around where Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia all meet, with a secondary population established around the Maryland area.

"Oklahoma, West Virginia, there's places where they have been found, but there's no population," Coyle explained. "Alabama is another one of those, up by Huntsville. They found one dead individual, so we're waiting to see if more crop up in that area."

Joro Spiders typically live right around a year, and they go through a lot of growth in that time.

The above photo is a baby Joro Spider, which is what they look like in the spring and early summer-- smaller than a quarter. This spider was one of 400 to 1,500 of the eggs its mother laid that made it through being a newborn.

If you've seen a headline or read an article calling Joro Spiders "flying spiders," it's a half-truth that these juveniles are capable of at this age.

They don't fly like a bee or bird, but instead, they make little web balloons and catch whatever breeze may be blowing.

READ MORE:Spring emergence: Beneficial insects for the South Carolina ecosystem

So "flying" isn't accurate, it's more like "ballooning," and a balloon at that is at the mercy of the wind.

They use the wind as babies to get dispersed," Coyle said. "Some can travel long distances that way, but from an evolutionary perspective that's a risky behavior. You don't get to pick where you land. You can land in a lake or a windshield, so the flying thing is also not really accurate, and the big ones, the adult Joros are not doing any ballooning.

That ballooning behavior also isn't unique to the Joro Spiders. A lot of spiders do this, something Coyle said no one ever even really sees because when they do it, they're typically too small to notice.

It's one of those things where every spring, there are probably hundreds of thousands of spiderlings looming over our heads every day and we have no idea.

If you've seen any of the pictures going around of the adult Joros, you'd understand why they couldn't be ballooning on breezes - they're pretty big.

It's not until the fall that Joros get to these sizes. With legs maxing out around four inches long, they can be a pretty intimidating-looking spider to many.

Despite its large size though, these spiders don't have much of a bite. All spiders have venom to some extent, it's how they hunt their food, but not all spiders have venom, or the fangs, to harm people.

I think the main thing to get across is if it's medically relevant," Coyle explained. "If you get bit by most spiders, Joro included, it's going to be annoying the same way a mosquito bite is. But if you get by a Cottonmouth? That's medically relevant.

The Joro also have no interest in biting you.

When you get down to the biology of spiders, it takes a lot of physiological energy to make venom, and to waste it on something you're not going to eat isn't a good strategy," said Coyle. "On top of that, a lot of spiders, their fangs probably aren't strong enough to puncture skin.

Though these spiders may not be a threat to people, they do pose an environmental concern, as all invasive species initially do.

SEE ALSO:Myrtle Beach crowned most moved-to city in 2024, study says

"We've already documented negative impacts from Joros. We started where their populations were high, and we checked what orb-weavers were there. Where there's high populations of Joros, there's nothing else," Coyle shared. "As you get farther away, you get more native species, so it appears that Joros just dominate everything in that way."

Some would say a spider is a spider who cares," Coyle said. "They're just as likely to eat a pest like a roach or a nice pollinator like a bee, but when you have a complicated ecosystem with a lot of species in it, and then you replace a bunch of factors with one factor in that ecosystem, it's hard to just know what's going to happen. Sometimes it takes a long time to learn what kind of impacts that may have, years and years sometimes. Are there impacts on native species? Yes. What's the impact from that? We just don't know yet.

Though Joros haven't made their way to establishing a population in the Grand Strand or Pee Dee, when or if they make their way here, they'll have some competition. Their cousin, the Banana Spider, is a similarly sized spider. They're both "orb weavers," which refers to the way they spin their webs, and they're both pretty intimidating-looking.

"What happens when the population of the Joros meets the edge of the population of Banana Spiders?" Coyle ponders. "That's going to be around Aiken, I-20, where Banana Spiders start showing up, so we're going to see what happens when these two really really similar species meet."

Before any orb-weaving turf wars break out though, Coyle has some advice for anyone who finds a Joro spider.

For starters, don't panic.

"I've never known anyone to get bitten, they're very docile," said Coyle.

Dr. Coyle also said it's important to recognize the difference between your local spiders and the invasive Joro.

Below is a photo of our two closest-looking spiders, the Banana Spider and the Garden Spider, also sometimes called a Writing Spider for the way they make a zig-zag in their webs.

I wouldn't tell anyone not to squash a Joro," Coyle says. "But they're not out flying around and hunting for people, there's no evidence they're dangerous to people or pets. They're a big, colorful spider that don't shy away from houses and carports, so they're in your face, but they're not dangerous.

For further reading on Joro Spiders and our local doppelgangers, click here.